Menu

- Undergraduate

- Graduate

- Research

- The Stretch

- Inclusivity

- News & Events

- People

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

Back to Top Nav

A Dartmouth-led study using a 600-year-old ice core shows that global mercury pollution increased dramatically during the 20th century, but that mercury concentrations in the atmosphere decreased faster than previously thought beginning in the late 1970s.

CRREL research chemist Sam Beal, PhD ’14, conducted the mercury research as a graduate student in Dartmouth’s Department of Earth Sciences. (Photo courtesy of Sam Beal, PhD ’14)

The study, conducted by Assistant Professor of Earth Science Erich Osterberg, Samuel Beal, PhD ’14, and their colleagues, found that concentrations decreased quickly after environmental legislation was enacted to reduce emissions in the 1970s. It was published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology.

The study suggests that current efforts to cut mercury emissions in the atmosphere reduce the emissions faster than most current models predict. It also suggests that future efforts to cut mercury emissions will have a larger impact on reducing pollution than previously thought.

The Dartmouth-led team analyzed an ice core spanning the years 1410 to 1998 from the summit of Mount Logan in Yukon, Canada. The team’s findings differ significantly from the emissions estimates that are used to drive global mercury models.

Assistant Professor Erich Osterberg says that mercury and other toxic metal pollutants have changed from the late 1990s to the present day. (Photo by Seth Campbell)

The new analysis showed that the first major mercury pollution peak occurred during the North American Gold Rush of the late 19th century, when mercury was used to extract gold and silver from ores and sediments. Fourteen percent of the mercury load in the ice core came from this time range.

It further showed that 78 percent of mercury pollution occurred during the 20th century, most likely due to industrialization in the United States and Europe. Mercury decreased through the late 1970s and 1980s as it was removed from many commercial products and emissions regulations were enacted in North America and Europe.

The ice core shows a renewed increase in mercury pollution since the early 1990s until the record ends in 1998 due to the rise of coal burning in Asia and small-scale gold mining in developing countries that is thought to have continued through at least 2008.

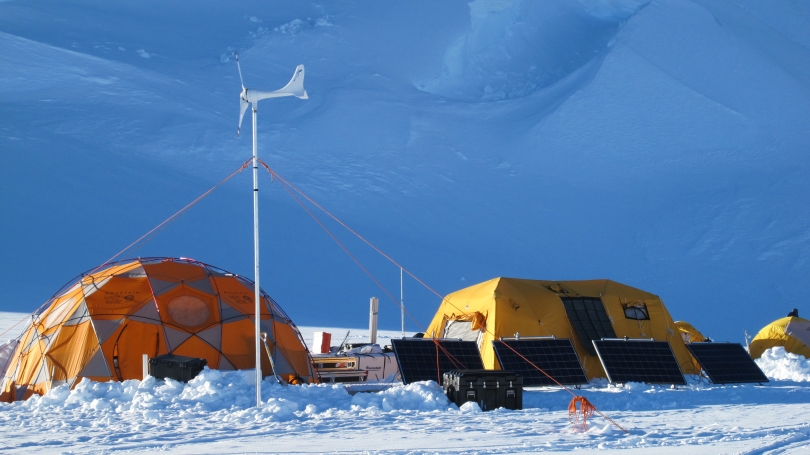

Osterberg and his colleagues will continue to study recent pollution trends from Asia using a new ice core collected in 2013 from Mount Hunter in Alaska’s Denali National Park and Preserve.

Read more:

“We want to see how mercury and other toxic metal pollutants have changed from the late 1990s to the present day,” Osterberg says. “The collection of new ice cores for this work demands urgency as glaciers around the world melt at an accelerating rate with warming temperatures.”

“The ice core record shows clearly how efforts to reduce mercury emissions have decreased pollution in the past. But the recent rise in mercury pollution from coal burning and small-scale gold mining show that there is more work to be done,” says Beal, who conducted the work as a graduate student in Dartmouth’s Department of Earth Sciences. He is now a research chemist at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory (CRREL) in Hanover.